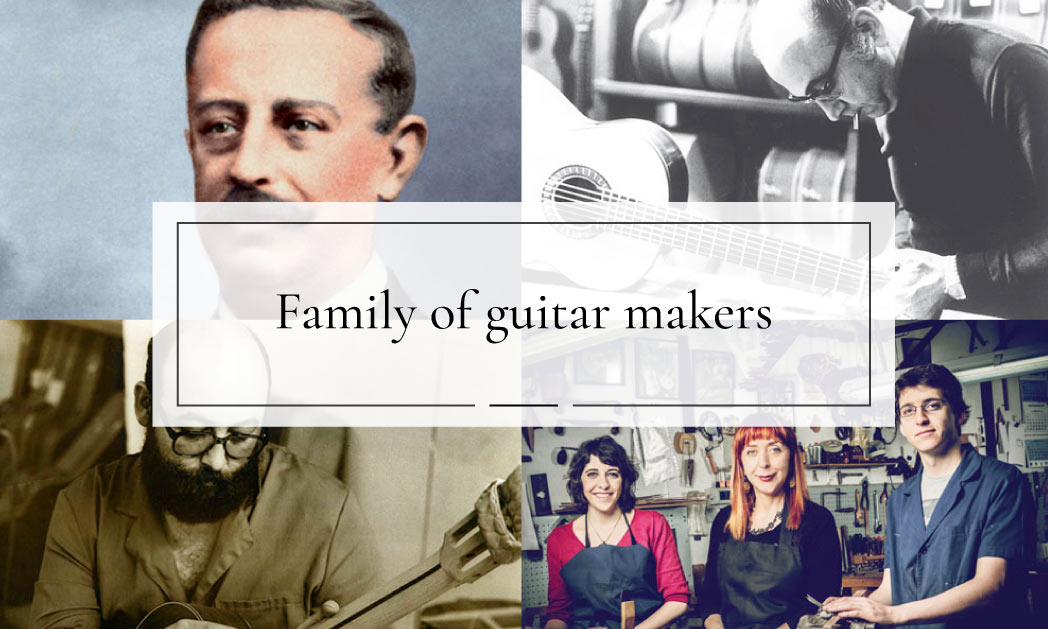

Given that my grandfather, José Ramírez II, was always rather uncommunicative, I can assure you that we have had very sketchy, not to say scarce, information about our family of guitar makers, in which there were – and still are – many gaps, information that partly collected by my father and partly complemented thanks to researchers who love the guitar, we have been filling in.

We believed that the love of the guitar-making trade began with my great-grandfather, José Ramírez I, who began his apprenticeship in 1870, at the age of 12; that he was the teacher of his younger brother, Manuel Ramírez de Galarreta. And that was the beginning of a great school of guitar makers in Madrid, a school of masters who also left their mark on the history of the Spanish guitar.

However, about three years ago, we received the news that the middle brother, Antonio Ramírez de Galarreta, had his guitar shop in Logroño, in Calle Mayor 52, around 1890.

José, Antonio and Manuel were the only three sons of Domingo Ramírez de Galarreta y Martínez de Abad, who was himself a great guitar enthusiast, as well as a builder and master carpenter. At that time, in Madrid, guitar makers also belonged to the wood guild. We believe that it is very likely that the fact that my great-great-grandfather Domingo’s three sons were guitar makers is because their father instilled this hobby in them, and why not, that he also built guitars, although he did not dedicate himself to it as a profession. He practised several activities, as in addition to those already mentioned, he was a landowner and horse breeder. Being a guitar maker, although an amateur, could well have been another of his activities.

So at the moment, we do not know how far back our family tradition of guitar-making goes. But to stick to what we can ascertain, we fix the beginning in the year in which my great-grandfather, José Ramírez I, began his apprenticeship with Francisco González, in 1870, although the foundation of his workshop was in 1882.

Passion for the guitar and music

In any case, our family’s love of the guitar was not only focused on its construction, since José also played the guitar, as can be deduced from the entries in one of his account books that we have preserved, which periodically shows his income from “guitar lessons”. As did at least two of his sons: José and Luis, who were also professional guitarists.

José, in addition to learning his father’s trade, at the age of 20 travelled with a group of artists to South America, hired as a guitarist, better known as Simón, or José Simón. As for Luis, he belonged to the Trío Español and later to the Trío Alpino, which played the lute, bandurria and guitar. We were informed about the existence of some wax cylinders with recordings of Simón and Luis Ramírez, around 1898 and 1905, when the brothers were still children.

The Tablao guitar

Flamenco tablaos and singing cafés began to spring up in Madrid at the end of the 19th century, making life difficult for flamenco guitarists, who were used to their small guitars that could be heard without problems in the intimate ambience of a room. But the voices of those guitars disappeared behind the clapping and stomping in those larger venues. And so it was that they came to José asking for a guitar with more sonorous power that would not be intimidated by their stage companions in the new venues. And so it was that José created the Tablao guitar, of which we have made a modern version based on my great-grandfather’s design, and which truly has a powerful and beautiful sound.

The relationship between José Ramírez I and Manuel Ramírez

JR I was, as I said above, the teacher of his younger brother Manuel. But due to life’s circumstances, and because it seems they both had a very strong character, they quarrelled and separated. For good. José settled in the Rastro, and later in Concepción Jerónima 2, and Manuel moved to Calle Arlabán 11. They never spoke to each other again, and each went his way without looking back.

There is a guitar that belongs to the collection of Félix Manzanero, which is a faithful example of the tensions that must have heated the atmosphere in the workshop that the brothers shared before the breakup. On the inside, there is a label that reads:

GUITAR SHOP

OF

JOSÉ RAMÍREZ DE GALARRETA AND BROTHER

BUILDERS

Address: Cava Baja 24.

And with the help of a mirror, you can see the stamp stamped several times, frantically I would say, on the inside of the lid, which reads:

GUITAR FACTORY

MANUEL RAMÍREZ

After the separation, Manuel continued to build the Tablao guitar, and little by little he modified it until he developed the flamenco guitar model that is still the reference today.

The Manuel Ramírez of Andrés Segovia

One day, while Manuel was in his workshop with the violin professor José del Hierro, he was unexpectedly, and fortunately, visited by a young man who wanted to rent a guitar to give a concert at the Ateneo two days later. Given the unusual nature of the request, Manuel decided to play along and left him a guitar to try out. On hearing him play, both José del Hierro and Manuel were amazed, and Manuel decided to give him the guitar as a present. This is a well-known anecdote, as the young guitarist was Andrés Segovia (I’m sure you’ve guessed it by now), and that legendary guitar is on display in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Manuel was the teacher of great guitarists such as Santos Hernández, Domingo Esteso and Modesto Borreguero.

As for JR I, as well as being Manuel’s teacher, he was also the teacher of his son José, and other renowned guitarists such as Enrique García and Francisco Simplicio.

José Ramírez II

José Ramírez II, 20 years after leaving for South America as a guitarist in a folk group, after having persuaded his father with some difficulty to let him go, with the promise to return in two years, a promise he did not keep, returned to Madrid after his father’s death, and took over the guitar shop. And he brought with him his wife, Blanca – a Spaniard from Zamora who emigrated with her mother and sister to Buenos Aires when she was still a child – and their two sons: José and Alfredo. She had the misfortune of living through the civil war and, even worse, the post-war period. Nevertheless, his great merit was to preserve guitar making and, thanks to him, we can continue the tradition.

He was the teacher of his son JR III, as well as Manuel Rodríguez and Alfonso Benito.

José Ramírez III

It is impossible to summarise José Ramírez III, my father, without skipping many things. He was a restless spirit and possessed a tenacity bordering on the most absolute stubbornness, which led him to carry out a large number of experiments, which Andrés Segovia tried out with patience and curiosity. There are many anecdotes about the relationship between Segovia and my father that would be too long to recount here.

The truth is that one of his main aims was to get Segovia to use a Ramírez guitar again. Of course, he succeeded, so much so that the only guitar he used for at least the last ten years of his life was a Ramírez, although he had already begun to use his guitars in his concerts long before that.

JR III left a legacy to the guitar world that is difficult to surpass, even though he always told my brother and me that our obligation and right was to surpass our predecessors – including him, of course – and he set the bar very high, which was part of his personality, as one of his favourite phrases was that difficulties harden the guts and he enjoyed constantly challenging not only his children, but anyone who got in his way, all of this always seasoned with an exquisite sense of humour. And like anyone who excels at something, he was as much admired as criticised, as much copied as refuted, to which he, paraphrasing Don Quixote, said: “ladran, luego cabalgamos” (they bark, therefore we ride), and went on his way.

He was the teacher of both my brother José Enrique – then José Ramírez IV – and myself. We both grew up hearing him talk about his favourite subject, the guitar, about his research, experiments, enquiries… and our daily life was impregnated with the smell of wood that he brought with him when he returned from the workshop… especially the unmistakable smell of the red cedar that he discovered for the use of the tops of his guitars. A wonderful character that I was privileged to have as a father and teacher, a teacher not only about the guitar but also about life.

He was also the teacher of numerous guitar makers, creating a great school of this ancient trade, teaching it to young people who entered, most of them, when they were practically children, and many of whom excelled later, after becoming independent, as in the case of Paulino Bernabé, José Luis Álvarez, Manuel Cáceres, Manuel Contreras, Félix Manzanero, Teodoro Pérez, Arturo Sanzano, Mariano Tezanos.

José Ramírez IV

As for my brother, José Ramírez IV – although he liked to be called José Enrique – he started building guitars around the age of 20. When he passed his exam to become a first-class officer, he had his acid test in the form of a trick by those in charge of taking the guitars that my father selected for Andrés Segovia, so that he could choose the one he liked best and exchange it for one of the ones he had in his possession.

The joke – loaded with malicious intentions, it must be said – consisted of surreptitiously including a guitar built by my brother among those destined for the maestro, so that by the time he realised it was already in Segovia’s studio and it was too late to remove it. So, in a nervous tizzy, he waited to see what would happen. I will clarify that his guitar – like all the guitars that left the workshop – was signed by our father, as is customary given that it was his workshop and his work, so the master had no way of knowing who had built it.

And, as it happens, he chose his guitar, so my brother, delighted as you can imagine, decided to give it to him as a present and wrote and signed a dedication that he glued next to the label. And this was one of Segovia’s favourite guitars, among all the Ramírez guitars he owned, and the one he played most often in his concerts.

This guitar, ten years after his death, was acquired by a Japanese gentleman, and my nephew José Enrique (at the time, José Ramírez V) and I had the joy of finding this guitar again during a talk we were giving in an establishment in Tokyo. I had just told this anecdote when, at the end of the talk, a gentleman came up to us and told us that he had this instrument, and he was carrying it with him so that we could confirm that it was my brother’s authentic dedication and signature, something that I could confirm without a doubt, since I experienced the whole story first hand, as well as being present when my brother wrote and signed the note, apart from being perfectly familiar with his handwriting and signature.

My brother died young. He had just enough time to perfect my father’s work by developing a system that made our guitars more comfortable to play and more stable in construction. He also convinced my father to design a studio line so that students and amateurs could own a Ramirez guitar at a more affordable price than our professional guitars.

My brother was also my teacher, especially in terms of knowing the business well, and thanks to him I have been able to run it when he was absent, although I still miss him both in good times and in difficult times.

Amalia Ramírez

As for me, I entered the workshop as an apprentice at the age of 23. Well, quite an apprentice in that way, because I started building guitars straight away, going off the beaten track. Probably because, as I was a woman and it was not foreseen that I would dedicate myself to this trade and even less to continuing a tradition that had always been for men, my father agreed to my request to enter the workshop.

After about three years, I left the business to pursue other activities and returned in the late 1980s to help my brother restructure and run the company. After my father’s death, and my brother’s a few years later, I took over the workshop, the office and the shop.

I have also done my experiments, among them making modifications to the flap of the Cámara guitar, developed by my father, and also creating the Auditorio guitar, built with a double top, also with a double back, and another variant by adding the double hoop. I made tests with the golden section. And I designed a semi-professional guitar that would create a bridge between the studio and professional guitars.

And finally, at present, I am half retired, so it is my nieces and nephews, Cristina and José Enrique, who are running the company in the front line, while I am in the rearguard, but doing what I can and serving as advisor and family memory.

Cristina and José Enrique Ramírez

The fifth generation, José Enrique and Cristina, are now the present and the future of this century-old company, and they share the work, although they share many things. For example, José Enrique is building guitars and teaching his sister Cristina the trade. He is in charge of programming the guitars according to the orders we have.

He and Cristina share the commercial area, with Cristina being more dedicated to this aspect, as well as to dealing with our guitarists. She is in charge of the social networks, and also of the design of the catalogues, posters, and brochures, as well as continuing to learn the craft of guitar making and supporting her colleagues in the shop when they need her… It has fallen to them to live in these “interesting times” that demand constant change and renovation, the challenge they have to face, as each generation before theirs has had to experience and deal with the challenges of our corresponding eras.

And they are doing it very well indeed, being a century-old, artisan business, out of time or beyond it, which has survived thanks to our ability to adapt, to our determination to carry on with the family tradition, and to our centuries-old and I would say genetic passion for this marvellous trade.

Article written by Amalia Ramírez.

April 2019